Home » 2013

Yearly Archives: 2013

Carefree car-free circular

Today being a beautiful clear frosty November day I decided that a bike run was called for. In view of my recent unsatisfactory run on the Dream Roadster, I thought a change of bike was in order, so I decanted several from their hiding-place under the stairs (it’s remarkable just how many bicycles you can fit into a confined space – there are another half-dozen in there besides these, and a few frames to boot)

I decided to take the 1934 Royal Sunbeam, but first I wanted to change the saddle.

Its current saddle is a hybrid, using an old B66 cover (with my favourite keyhole slots and oval Brooks side-stamp) perched on a set of triple-wrought springs I’ve had for ages. Unfortunately, the cover (an eBay purchase) had suffered a makeshift repair, leaving it with a loose and awkward rivet at the rear (nearest the camera); it has also nearly reached the limits of its tension and begun to sag, so for all its handsome appearance, it is not the most comfortable ride.

Removing the old saddle revealed an interesting feature of the Sunbeam, a closed-end seatpost. When were these introduced, I wonder? Presumably there is some notion of protecting the inside of the seat-tube.

I decided to fit the mystery saddle, which has now been identified with some degree of certainty as a Lepper – originally a German firm, as I now know, so that finding a similar saddle on a pre-War Goricke bicycle (also a German make) was not so remarkable. Many thanks to Rona Dijkhuis of the Slow Bicycle Movement and Maarten Bokslag, Chairman of De Oude Fiets (whom I contacted at Rona’s suggestion) for their help in my quest to identify it, detailed here.

I opted for a rather forward position for the new saddle, purely as an experiment – my older Sunbeam, a very comfortable bike to ride, has a ‘gallows’ type seat post which brings the seat a little further forward and more over the pedals, so I thought I might replicate that. In view of the new saddle and the experimental seat position, I reckoned a leisurely run was called for, with nothing too strenuous, so I decided to head into town and pick up the lade-side path. It was only when I paused for my first picture that I realised I had left my camera sitting on the garden seat at home (I had been distracted by fettling a loose rear mudguard).

I had ridden some way before I remembered that I had a camera anyway, in my phone. I was glad of it when I came to the point where the ladeside path has to cross the railway, because I was able to record this simple but effective aid to cyclists, an iron rail running up the side of the steps:

it mounts up one side

and down the other

and does the job it was intended for admirably (though you need a firm restraining hand or even a touch of brake on the descent). I missed this turning the last time I was out this way, so it was a pleasure to find a lengthy new stretch of the ladeside path. Though it is generally well-maintained with a tarmac surface, there is a pleasingly rougher section a bit further on:

However, after following this part, I lost my way again – I had hoped to pick up the N77 national cycle route at Almondbank, though this involves an unsatisfactory crossing of a motorway bypass; but the route I followed petered out among houses and an industrial estate (if you consult the map, you can see where I went wrong, round about Edradour Terrace) and I ended up going back towards town and joining the N77 route via North Muirton. Heading along the banks of the Tay, my eye was caught by a large dark bird perched out in mid-stream. From its distinctive beak and greenish-black sheen, I took it to be a cormorant, possibly one I had seen before on the South Inch pond some time ago and recorded in this rather poor picture:

Unfortunately, the camera phone is not very good for this kind of thing – the bird can be seen here in the left middle ground, looking a bit like the celebrated ‘surgeon’s picture’ of the Loch Ness Monster:

while here it makes rather a nice impressionist blur:

This stretch of the Tay looks well at this time of year:

Some way further on I posed the bike with some street furniture with the bridge in the background

then headed off along the broad Tay St pavement and on to the South Inch, crossing by the fine diagonal avenue:

and so home, after a largely car-free seven-and-a-half mile circuit of Perth (see route here). All in all, a much more satisfactory and uplifting trip than the previous one, detailed here. How much was that due to me, how much to the choice of bike and route, how much to the absence of wind? it is hard to say; anyway, it was much better.

And the new saddle? Already a firm favourite.

‘Blow, blow, thou winter wind!’

‘Walking for exercise? Pah!’

My father had a way saying ‘Pah!’ that was peculiarly dismissive. He liked a good walk, so it seemed an odd thing for him to say, but I think it was his very love of walking that made him say it. To walk ‘for exercise’ carries an overtone of duress, as if the person would sooner not be walking at all, but feels obliged to; it is as if all possibility of enjoyment has been removed beforehand – ‘I only do this for the exercise, you know.’ It was the grudging attitude that my father contemned.

A recent excursion on the Dream Roadster prompted that memory of my father: it was a ride I did not enjoy, I think in part because it was undertaken grudgingly, out of a sense of duty. In an endeavour to bring some order to my chaotic existence I had resolved to adopt some regular habits, chiefly in relation to my writing. Among them was the resolution that I would make at least one cycle excursion per week and write it up here. By Thursday I still had not done it, and since the day seemed fair enough for the time of year, I forced myself out.

Cycling is often, for me, a deliberate antidote to the melancholic lethargy to which I am prone, so it is not unusual to have to chide myself into it: ‘you’ll feel better for having done it; you know you’ll enjoy it once you’re out there.’ It generally works, but not always (and I was interested to find Lovely Bicycle blogging on much the same point, here – could it be the time of year?). The day was bright enough, with flaring Autumn colours

and I went by the usual secret paths

I rode up over the hill and down into Strathearn, pausing to admire the Earn on either side of the eponymous bridge:

but for all the beauty of the scenery the calmness of soul I was seeking (perhaps too determinedly) refused to manifest itself. Instead, I found myself annoyed with my bicycle: the saddle was not high enough, the handlebars were too low; it just didn’t seem right. Then there was the road: it was altogether too straight

in both directions

yet it was not easy cycling: for all the seemingly straight and level ground, I found I could not deploy my lordly hundred-and-fifty inch top gear and toiled along in the middle ranges. Only gradually did it dawn on me that I was battling an invisible adversary: there was a steady headwind.

I am not a much of a man for getting wet – though there is a certain pleasure in defying the elements if you are dressed for it – but given the choice between wind and rain I think I would choose the latter. Rain is honest; wind is insidious. You know it more by its effects, as in this case, where a level ride seemed like toiling up a steady gradient. It is dispiriting; you are conscious of making less headway than you should, yet the cause is not apparent – it is not the wind you feel, so much as a resistance.

And having set out in what was not the best frame of mind, this soured my mood still further. Why was I doing this? Where was I going?

The answer to the second question was ‘nowhere in particular’ : I had resolved to investigate the road in the direction of Longforgan and Forteviot, partly as a scouting mission for some future attempt on the Ochil glens, though I did not think I would attempt the first opportunity for that, over the Path of Condie, which is steep and twisting.

(While I was taking the picture (badly – I know) the white pick-up truck came past, stopped, then reversed to where I was. The driver peered out and laughed, saying he had mistaken me for someone else – ‘I thought I knew the only cyclist who would stop to take the picture of a road sign’. I assured him that every cyclist has the urge to take pictures of roadsigns. I wonder if that is true? I remember when we were young my brother and I mocked our father’s penchant for taking pictures of roadsigns on our Irish holidays; yet now it seems perfectly sensible: few views are so distinctive in themselves as to be instantly recognisable; there is nothing quite so local and particular as a roadsign)

I toyed with the notion of making a circuit by turning North across the railway line and joining the Aberdalgie-Craigend road that featured in my earlier excursions here and here, but eventually I resolved that enough was enough: I would simply turn back. When the road swung round at the junction with the Invermay road,

I decided that the splendid view of the distant hills that opened up was reward enough for any outing.

Heading back with the wind behind me I was able at last to use my mighty top gear, and went bowling along at a swift pace while pedalling in a leisurely manner. An ample pavement allows traffic-free cycling from Bridge of Earn to the Craigton interchange, with magnificent Autumn colours

And the Tay from the top of the Edinburgh road is one of the pleasantest approaches to Perth

though in this case I was not quick enough to catch what had caught my eye, the unusual sight of a boat in mid-river – by the look of it, probably a semi-inflatable of the kind the fire service use.

So home at last, after a trip that seems pleasanter in remembrance than it was in reality, though that perhaps is because it is overlaid with the memory of one I have done since – just before writing this, in fact – which was altogether more satisfactory and uplifting.

And later in the evening there was a splendid moonrise, pictured at the top.

The route for this journey is here.

The Dark Secret of Pottiehill

All right, I can see you’re not convinced: how can a place called Pottiehill have a dark secret? Yet it does; I have seen it. I have pictures (though some of them are a little odd – an unfamiliar camera).

But first, the curious case of Benjamin Button. (you see what I am doing here? Suspense! The craft of fiction)

Some time ago I pondered the need for an improved gear set-up on my Dream Roadster. In a flurry of energy I actually obtained the necessary 14T cog,

– which is a good deal smaller than the 18T it replaces –

I fitted it (with the usual pantomime of levering off spring clips with screwdrivers and wondering where they will fly to – but at least I had the good sense to wear eye protection)

and set out, only to find, to my chagrin, that somewhere in the few hundred yards I had travelled from the house I had lost the changer button on one side of my Schlumpf Mountain Drive.

I retraced my steps several times, back and forth, but to no avail; so there was nothing for it but to ring Ben Cooper at Kinetics – a splendid shop in Glasgow where I got the Mountain Drive originally, many years ago now – to see if he could supply a replacement. He could, but of course that meant a further delay.

The button comes with its own delicate Allen key, used to secure the tiny grub screw in the centre against the end of the changing rod, where it acts (as far as I can see) rather like a lock-nut.

Though I tightened it vigorously as advised, I am still nervous of losing it again – I wonder if a set of natty leather gaiters (perhaps in matching red) designed to fit the top end of the crank would bring peace of mind? Something to ponder, perhaps even make, in the long winter nights.

In the meantime I obtained another replacement, for my Lucas Mileometer (or Odometer, if you will) which disappeared in the course of my last major excursion – the same one that convinced me my gear set-up needed changing.

But to our tale: it being a fine class of Autumn day for the first of November – All Saints’ Day – I resolved to make an excursion. Not only did I rig the mileometer, I also transferred my ferociusly powerful Smart BL201 headlights (powered by a rechargeable lead-acid battery) from the 1923 Royal Sunbeam. Here we see them blazing futilely against the light of day, ‘crying like a fire in the sun’ as Bob Dylan might say:

Why the lights? Well, if you are off delving into dark secrets, it is wise to have some; I also took a torch, being unsure that I would be able to take my bicycle where I was going. You may notice that I have repositioned my trusty Lidl handlebar bag behind the bars to accommodate the lights, but this proved impractical, as my knees hit against it, so after a short distance on the road I transferred it to the saddlebag position.

I set off over the hill by the Edinburgh Road and down into Strathearn. There had been a heavy shower of rain while I was working on the bike, but the weather was clearing steadily, with sunlight on the distant hills.

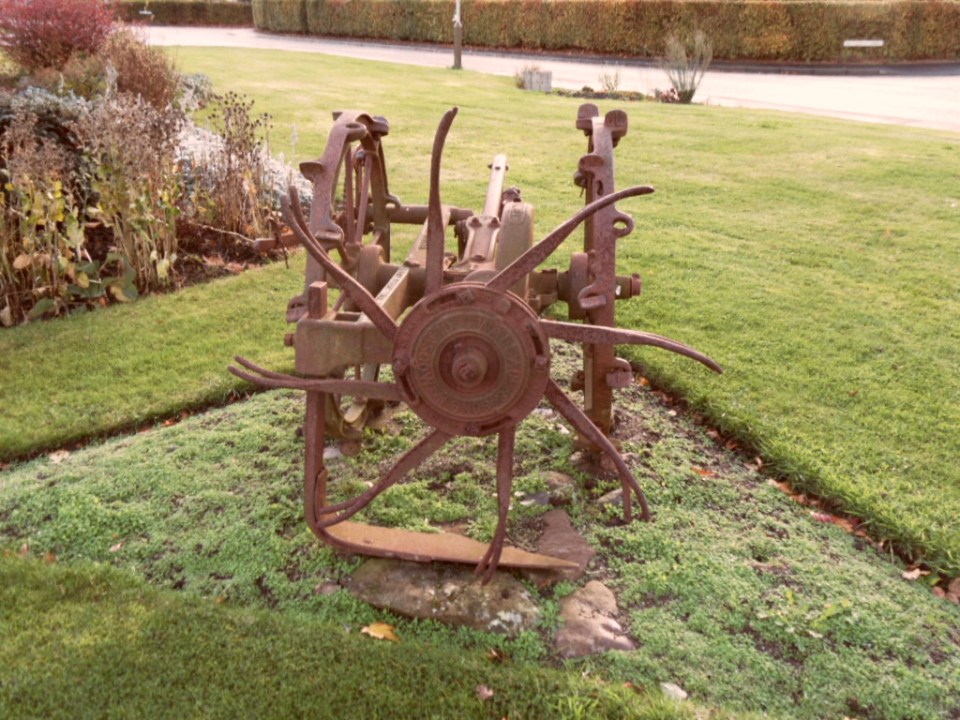

In Bridge of Earn I paused to take some pictures, first of a signpost, then of a curious agricultural implement on display near by.

Then off I went along the Wicks o’ Baiglie Road, which once upon a time was the smart route to take if you were driving to Edinburgh and there was a lot of slow-moving traffic ahead: you knew you would never pass it in the tortuous passage of Glenfarg, but if you belted over the Wicks o’ Baiglie you might well beat it to the other side. These days are gone now, since the M90 motorway now bypasses Glenfarg altogether. But how was my new gear set-up, I hear you cry, plaintively. Very good, I am happy to say, though I did lose my chain very early on ascending the Edinburgh Road; the Mountain Drive in low gear under stress seems susceptible to any variation in chainline. Happily there was no repetition, and I found that I was glad of even my lowest gear ascending the Wicks o’ Baiglie Road, seen here looking back – a long steady mercilessly straight climb:

Earlier, on the flat, I had tried out my Lord-of-Creation one-hundred-and-fifty-inch top gear and found it every bit as delightful as I hoped: you bowl along at tremendous speed, yet pedalling in a slow and stately manner. However, I was a little wary of the quantities of wet leaves – a notoriously tricky surface. At another point there was a constant crepitation as I cycled through beech-mast: the sounds of Autumn.

The first sign of my destination was the remains of what had been a railway over-bridge looming ahead:

On the other side of it I found a gate which was locked, so I lifted the bike over but was content to duck myself through a large gap in the wire fence, as befitted my years and diminished athleticism.

And there I was, on what was once the North British Railway line from Mawcarse Junction to Bridge of Earn via Glenfarg. A distant tree caught the sun and blazed out bright gold, which I took to be a happy augury; there was also a rainbow, and a splendid buzzard which flew up from right to left, which the Romans would doubtless have deemed auspicious.

The line was closed in January 1970, having evaded the Beeching axe, probably because of the proposed route of the M90, mentioned above. It must have been a pleasant one to travel, fairly high up one side of a broad valley at this point, with fine views across to the confluence of Strathearn and Strathtay.

I cycled on through pleasant Autumn woodland, past a great stack of felled timber

And then up ahead, there it was, the dark secret of Pottiehill:

This is the northernmost of two tunnels, each about 500 metres in length, which took the line from Glen Farg across into Strathearn.

I like tunnels. My first serious experience of them was not on the railway (though I have been through many, I am sure, but in a train it is just a darkness) but on the more ancient transport route of the English canals, where there are some splendid and very lengthy tunnels. Transiting a tunnel in a narrowboat is an eerie experience: you are surrounded by dark, with only a narrow horsehoe of light some sixty feet ahead, thrown out by the small bow light, which is not so much for illumination as to let others know you are coming. The first few times I did it I suffered the consistent hallucination that I was actually in a much vaster space, and not the narrow confines of a tunnel just wide enough to let two boats pass one another and just high enough to give them clear passage. (My canal tunnel experiences found their way into my writing – in my third published book, City of Desolation, my young hero Jake finds himself on a Dantesque journey through Hell, which has evolved somewhat since Dante’s day, having acquired (among other things) an underground canal system – see here)

The Pottiehill tunnel is a fine feat of engineering and the interior for the most part is dry and entirely sound; the ground is a little uneven, but is not difficult to cycle, though I was glad of my powerful lights, as the tunnel has a considerable bend so that you cannot see the far end and the near one at the same time.

I had heard tales that these tunnels had been used to store old steam locomotives as a precaution against nuclear war (the reasoning being that a steam engine would be easier to fuel than a diesel in the disruption that followed) but I think that is just wishful thinking on the part of old steam men and romantic civil servants. In this case it would not be terribly practical, since the line has been taken up, and as far as I know, the tunnels (unlike some others) have never actually been closed off.

I emerged from the North tunnel onto a pleasant stretch of overgrown trackbed running between autumn woods, but it was very muddy underwheel and for some distance was in fact the bed of a stream; but this is the kind of thing that imperial roadsters take in their stride. I would not attempt it on a narrow-tyred mount. After some distance I came on a conundrum: the main path rose steeply to the right, with a more overgrown fork descending to the left.

I dismounted and tried the upward path, but had not gone far before reason told me it was much too steep for any railway line. So I turned back, left the bike, and made my way ahead on foot.

The path was not cyclable: it was criss-crossed with fallen trees, and in places was very boggy.

But I persevered and was rewarded with a sight of the North portal of the South tunnel, though it did not look exactly like this:

I went through with the aid of my torch, and again found the surface dry and sound.

There is the rusted shell of a car at the Southern end; I was expecting it, as it is mentioned on various websites; but I still wondered how it got there.

A little way beyond the tunnel, a fine viaduct crosses Glenfarg, and down the side you can glimpse (a good way below) the river Farg and the road running beside it.

I crossed the viaduct and went as far as the gate that bars it; the line runs on invitingly,

while looking back you have a fine view of the South Portal across the viaduct

but for me it was time to turn back. At the South Portal, I came on a strange fellow hanging around:

The South tunnel is straight enough to see both ends from the middle, though you need to stand to one side, so it clearly has a bend in it. I went back through without using the torch, just for the fun of it. It is surprising, once your eyes get used to the dark, just how much you can see, and one thing you notice is how any surface that faces the tunnel mouth behind you catches the light. In honour of my brother Brendan, who instituted a tradition of tunnel-singing on the canals, I tested the acoustic with a verse of the Tantum Ergo. Fortunately there was no-one else to hear.

Emerged on the other side and reunited with my bike (I had chained it to a tree – doubtless an unnecessary precaution, but peace of mind is a great thing)

I made my way back through mud, stream and tunnel,

pausing to snap a harrow sheltering in the North portal, like the remains of some giant insect or alien creature

I think that my attempts to take pictures in the tunnel must have confused the automatic settings, because the shots I took after I emerged had an odd sort of old-fashioned-postcard quality to them, like this vista of Strathearn meeting Strathtay.

I saw that there was an alternative route off to the left and hoping to avoid the gate I took it, only to find I had miscalculated somewhat – to my surprise, instead of rejoining the road a little further up the hill than I left it, I found myself swinging right and passing under a substantial bridge that I had not realised was there; yet I must in fact have crossed it. The reason for it was clearly the stream that I was now cycling alongside, with the road I wanted on the farther side. However, I was not too perturbed, reasoning that a well-made track must lead somewhere, and it was heading in the right general direction. A little way on I came on some substantial but derelict farm buildings, which had the haunting quality all such buildings have, enhanced in the picture by the weird colour setting, which nonetheless captures the atmosphere surprisingly well

Carrying on for some way I emerged at last onto a side road; a sign at the point where the track debouched informed me that it was a private road with no vehicular access, so had I come on it at that end, I probably would not have gone up. As a matter of fact, the way I went is more direct and easier, apart from negotiating the gate, but this was a very pleasant return route.

The light was failing rapidly, not so much from the onset of night as the weather, but as I had neglected to rig a rear light with my headlights, not thinking I would be out so late, I made one more stop for pictures then headed home.

All in all, a most satisfactory excursion and a sovereign specific for driving away melancholy. The route can be seen here.

Saddle Mystery Solved?

Well, maybe…

This is an interesting lesson in communication – how can you receive a clear and definitive answer to a question and still doubt whether your question has been answered at all?

In the summer, as detailed here, I bought a handsome but anonymous saddle on eBay. Then the other day I came across this, in an online auction catalogue:

What struck me at once was the stamp on the side, with its ‘Greek key’ border and flanking pair of spoked wheels, which apart from the insert where the name appears, is almost identical to mine:

In addition, the unusual-shaped cut-outs are also strikingly similar, as is the small detail of the location of the rivets, along the face of rear edge rather than the top of it, as Brooks do:

Now Lepper are a Dutch company, still very much in the saddle-making business, so I e-mailed them some pictures and asked if they thought mine was also a Lepper saddle; and this morning received this succinct reply, which I reprint in its entirety:

‘This is a Lepper Drieveer 90 saddle’

So, mystery solved, then? Well, I am not so sure. The problem is that (thinking it might be helpful to present the evidence that had led me to my conclusion) I sent pictures of both the Lepper saddle on the auction site and my own, with the auction site picture first.

My suspicion is that the kind but busy folk at Lepper have looked only at the e-mail title (‘An old Lepper saddle?’) and the first picture and identified that – for which I thank them, but it gets me no further forward. (“Drieveer’ is ‘three spring’, I believe, so does not help distinguish the two). It may be that I malign them, but I did send them a link to the original post and I notice that there has been no Dutch visitor in the time between my e-mail and their reply.

However, I do feel that the similarities between the two are strongly suggestive of a common origin, but on the other hand it might be a case of deliberate imitation – the substitution of a decorative pattern for the (expected) firm’s name would point to that. On the other hand, mine is no shoddy article – it has been expensively made, and in one thing at least – the triple-wrought springs – it appears superior.

An interesting side note is the use of ’90’ to designate this style of saddle. It is used by Brooks, of course (originally just B90, then a range of models B90/1, /2 & /3, which I think varied slightly in size) and I am sure I have seen it on other British makes such as Wright and Middlemore. Did Brooks start it and the others follow suit, or is there some other reason for it?

Gearing dreams and reality (another one for epicyclists)

Sometimes, you do not fully appreciate why something is the way it is till you try to do it differently (as a writer and a lover of books, I hope that may be the lasting effect of e-readers such as the Kindle: they will make people appreciate just what a clever piece of technology a book is – but that is by the way). My Dream Roadster, as its name suggests, is an attempt to realise an ideal form of the Imperial Roadster bicycle by retaining its desirable features while overcoming its shortcomings, principally in gears and brakes.

In practice, I have found that the Dream Roadster has served mainly to deepen my appreciation of the production Imperial Roadster, in particular the two versions of it that I own, a pair of Royal Sunbeams. The matter of braking systems I will consider another day (the Dream Roadster has drum brakes, where the standard Imperial has rod-operated rim brakes) – but my excursion earlier this week , which involved the strenuous ascent of Necessity Brae on my 1934 Sunbeam,

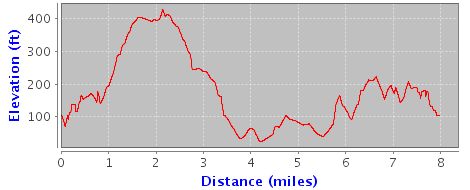

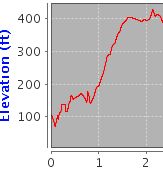

revived a question I had asked before, how many gears does a man need?. The Sunbeam’s low gear is around 54”. I had managed to climb the hill in that, though it took a deal of effort and determination – at several points I had thought about stopping, but had willed myself on. Evidently, then, a lower gear would make things easier, but how much lower should it be? That was the question I set out to answer the next day, when I repeated the same route using the Dream Roadster.

The Dream Roadster has a five-speed rear hub (SRAM/Sachs P5) coupled to a two-speed bottom bracket gear, a Schlumpf Mountain Drive. On the present set-up, this gives nine distinct gears (two are duplicates) – a normal range of (approximately) 47”, 58”, 75”, 96” and 118” with a lower range of 19” 23” 30” 38” and 47”. My guess, from previous experience, was that the lowest useful gear would be the 30” one so I resolved to put that to the test. Before setting out I made a couple of trial ascents of hills near by, Glenlyon Rd

and Quarry Rd

which confirmed my suspicions: the 19” is effectively useless – though it offers virtually no resistance, the speed at which it must be turned to make even the slightest headway requires a far greater effort than walking, for less return. The next gear up – 23” – is only marginally useful as it still requires to be spun at a higher rate than I find comfortable to achieve a forward progress less than walking pace.

So I set out to repeat the trip of the day before (map 4 here) with a minor variation at the start – a new secret way such as Craigie (the district of Perth where I live) abounds in

My aim was to use 30’’ (the mid-gear of my lower five) as my lowest gear. The ascent of Necessity Brae was still strenuous,

but less so than the day before, and at one point where the slope lessens I actually changed up to the 38” gear for a time. Though I already knew I could ascend the hill in a substantially higher gear, my aim was to find the most practical lowest gear for the Dream Roadster, and the answer to that appeared to be around 30”.

This was borne out by the fact that I continued without dismounting, save to record the occasional rarity –

and some wild flowers here and there:

(it’s nice, with the hedgerows so dominated by red, to find a touch blue and purple)

I even managed the sharp ascent to Craigend which had undone me the day before, though this time I was expecting it. I returned as I had previously, with occasional stops for blackberries and to record the onset of Autumn,

(a sight that recalled a line from Eliot: ‘the communication of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living’)

and so home via another secret way:

The one casualty of the trip was my mileometer, which I must have shed somewhere along the way (I did have to stop at one point to adjust the front wheel, which had slipped, so I think it was some time after that – I retraced my route on foot next day, but to no avail).

So, the conclusion to be drawn (besides the obvious one of checking the tightness of all fixtures before setting out) is that around 30″ is as low a gear as I need. However, once I fell to my calculations, I found a familiar problem. An earlier version of the Dream Roadster had coupled the Mountain Drive to a 7-speed SRAM/Sachs hub, giving 14 gears with a spectacularly wide range of 763%. This setup was arrived at before I ever built the bike and sprang from a couple of simple-minded comparisons – the fabled (and fabulously expensive) Rohloff Speedhub had 14 speeds but a range of ‘only’ 526%, so an arrangement that was cheaper but offered the same number of gears over a wider range had to be better, surely?

In practice, I soon encountered the difficulty I describe above – the lower end of the gear range was something like 17, 20 and 24 inches – of which only the last was even marginally useful. This led me to conclude that the SRAM/Sachs 7 speed hub offered an adequate range in itself, so I swapped it for the SRAM/Sachs 5 speed I had installed in my daughter’s bike, giving us both (I hoped) a more useful range of gears.

However, setting 30” as a bottom gear with the P5/Mountain Drive combination and a 28” wheel implies a direct drive of some 119”, not only ridiculously high in itself and giving an unfeasibly huge 188″ top gear, but requiring a gear ratio (front to back) of 4.25:1, meaning that a 48T chainwheel would need an 11T sprocket (impossible to obtain for a hub gear – 13T is the smallest I have come across). With 13T at the back a 55T chainwheel would be required to maintain the same ratio.

The upshot is that I have ordered a 14T sprocket which, with the present 48T chainwheel, would give a gear ratio of 3.4:1, meaning a direct drive of c95” and a lowest gear of c24” – still barely useful. The full range would be (approximately)

lower: 24, 30, 38, 49, 60 upper: 60, 75, 95, 122, 150

I look forward to testing that – the long-striding twelve-and-half foot top gear should be fun* but I have to admit that I am already toying with the notion that for my purposes six gears might be enough – using the same 14/48 set up with a typical 3 speed would give me approximately

lower: 28, 38.5, 52 upper: 70, 96, 131.

That gives a bottom gear much closer to my tested useful minimum and makes an interesting comparison with the fabled six-speed Sunbeam of 1908, which offered 49, 66, 72, 88, 96, 129:

(photo by kind permission of Leon Wise)

Some might object to the increasingly wide gaps in my upper range but I think that is a matter of taste and cycling style. The justly-celebrated Rohloff offers 14 evenly-spaced gears (at 13.6% intervals) but for me that is an epicyclic hub brilliantly conceived to do the same job as a derailleur, only better – it’s all about maintaining cadence, keeping the same input and varying the gear to suit.

Riding a roadster bicycle is about varying input to suit the conditions: you are prepared to labour up a hill, or even dismount and walk, knowing that eventually you will reach the top and be able to freewheel down the other side; and on the flat, there is no more lordly feeling than to sweep along at great speed by turning a tall gear at a dignified, leisurely pace. Large steps between high gears are not a problem as you only use them when you are already travelling at speed; it is in the low gears that you want to avoid the jarring shock of too wide a gap.

Around 70 inches was the common single-speed gear for the Edwardians, who liked to calculate at 10 gear inches for each inch of crank, and regarded 7” cranks as the standard. I reckon that a future 6-speed Dream Roadster with the set-up above would give me in one bike the equivalent of two three-speeds, one well-suited to the hill country, the other formidable on the flat.

I have to say I’m sorely tempted…

* 13 yards on the road for a single turn of the pedals, or better than 26mph at a modest 60 rpm – though I expect wind-resistance would be a factor.

Autumn circular with brambles, hips & haws

(The map for this route can be found here)

Well, after a dull morning, the sun came out and so did I. Early on it had shown all the promise of a classic Autumn day – bright sun, a nip in the air, trailers of mist on the hills – but then it all went grey and I thought I wouldn’t bother. Then in the afternoon the clouds dispersed and I though it was too good a day to waste indoors. I found with shame that both my serviceable mounts – the Dream Roadster and the 1934 Royal Sunbeam – needed air in their tyres. Was it so long since I had been out?

After a brief consideration I chose the Sunbeam: it suited the day better, somehow. Before setting out a buzzing made me look up and there was a microlight enjoying what must have been a beautiful view. You need good eyes to see the microlight, but I like the accidental saltire made by the wires – and what a fine sky!

What route to choose? I decided to take the old road to the West out of Perth which starts with a long climb called Necessity Brae. This makes a fine pairing with the splendidly-named Needless Road, which runs off the Glasgow Road into Craigie. To get there, I decided to take the route round Craigie Hill – it being the especial pleasure of the cyclist to go by secret ways and strange, where motor cars cannot.

This path swoops around the base of Craigie Hill under a leafy canopy for much of the way:

Necessity Brae is a strenuous climb in low gear but a merciful bend hides the upper section and keeps you going. This is the view looking back to Perth

at the top, you are rewarded with brambles, or blackberries, if you prefer.

They never tasted better: solar-powered Blackberries.

And here we see that great rarity, a Sunbeam recumbent:

It’s a good viewing point – you can look North East, across to Strathmore, with Kinnoull Hill on the right,

or North to the Grampians

The Brae takes you up out of Strathtay, the valley of the Tay, and over a shoulder of land to Strathearn, the broad and splendid valley of the Earn.

There is a fine descent into Strathearn, but age brings caution: I enjoy going down hills, but no longer at full-tilt as I did in my youth. I find the conviction that I am immortal has weakened with the years.

Once down, I swung back Eastward towards Craigend and so to Perth.

There are a couple of handsome railway bridges over the Earn, where the lines out of Perth branch South to Edinburgh and West to Glasgow. This is the Westward route:

and this is the Southern route, marching away across fields of gold, while the Western route runs across the middle ground:

A fine bush of red berries made me think of Seamus Heaney and The Haw Lantern, though these I think were hips.

Further on I found what I think were haws, but I am open to correction. My father told us often on country walks, but alas! I did not heed him well enough.

Approaching Craigend I was surprised by a stiff ascent and exercised the first rule of cycling, ‘it’s all right to walk’.

Remounting, I joined the main road from Edinburgh to Perth, a short climb over the same shoulder I had crossed earlier in the opposite direction. I passed a fellow-cyclist enjoying his share of brambles and really should have been sociable and stopped but I was eager to be home (why? there was no rush) so made do with an exchange of greetings. I caught a glimpse of the classic view of Perth coming from the South East but I fear the picture does not do it justice:

And so home again, feeling as always much the better for having been out on my bicycle. What better way to spend a fine September afternoon?

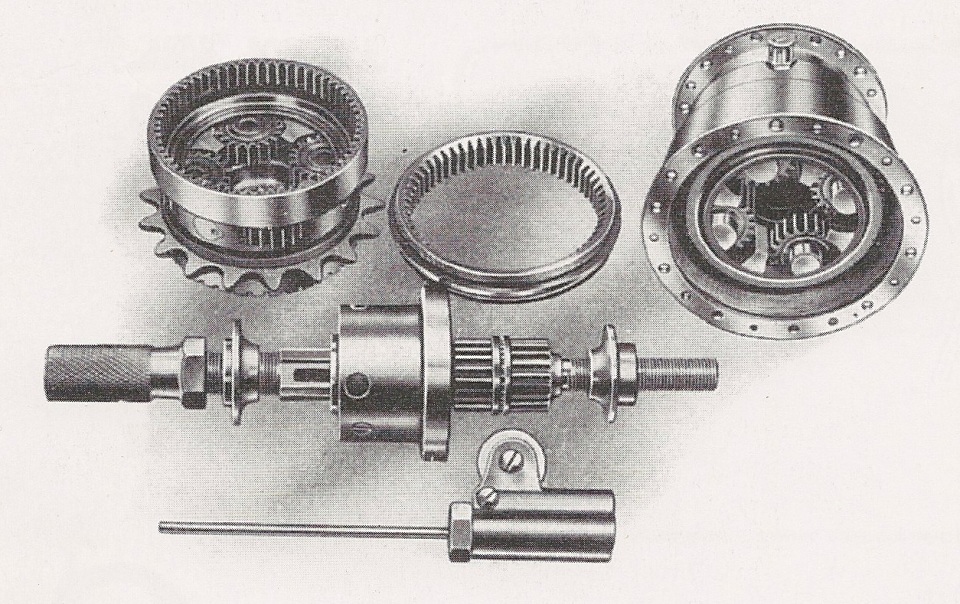

The Great Sausage Mystery – or why Sunbeam abandoned the Newill Hub

You find answers in the oddest places*; sometimes to questions you hadn’t thought to ask till you came across them. I have already written about my adventures dismantling the William Newill-designed Sunbeam 3 speed hub; a recent article by Robert Cordon Champ, the Sunbeam registrar at the V-CC and the author of Sunbeam Bicycles & Motorcycles, raises the question of when the Newill hub was discontinued. In researching that, I came across what may be the answer to a more interesting question – why was it discontinued?

There never was a Sunbeam Cycle Company – Sunbeam cycles were made by John Marston Ltd, set up in 1895 and headquartered at Sunbeamland in Paul St, Wolverhampton; their components such as pedals and gears were made by Villiers, the company set up in 1898 under John’s son Charles in near by Upper Villiers Street. John Marston’s foreman, later to become his business partner, was William Newill.

Newill’s name, along with John Marston Ltd and James Morgan (the cycle works under-manager) appears on the 1905 patent for a three-speed epicyclic gear. In view of what follows, it is noteworthy that the primary application (and the first illustration) shows the patent as a bottom-bracket gear; its application to the ‘driving-wheel hub’ is only mentioned in passing. Sunbeam already had a two-speed bottom-bracket gear, introduced in 1903; it continued in production till 1932. However, no three-speed version of the Sunbeam bottom-bracket was ever made – the only such articles on record are one by the Allen Company, mentioned as being ‘in the experimental stage’ in 1907, and another offered by the James Cycle Co in 1909 (by which time the Allen had disappeared) – and it is not certain if that was ever marketed.

Hub gears, on the other hand, were in abundance: the first decade of the twentieth century was their Golden Age, and the year 1909 its zenith. The Sturmey-Archer 3 speed (really William Reilly’s design, as Tony Hadland has shown) was introduced in 1902; by 1907 you could choose from nine two-speed hubs and seven three-speeds; in 1909 there were eight two-speeds and no fewer than fourteen three-speeds, although four of these were Sturmey-Archer designs.

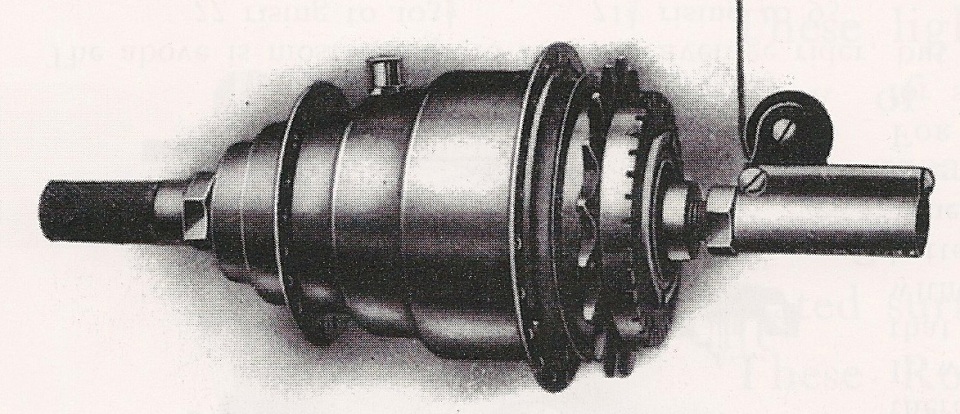

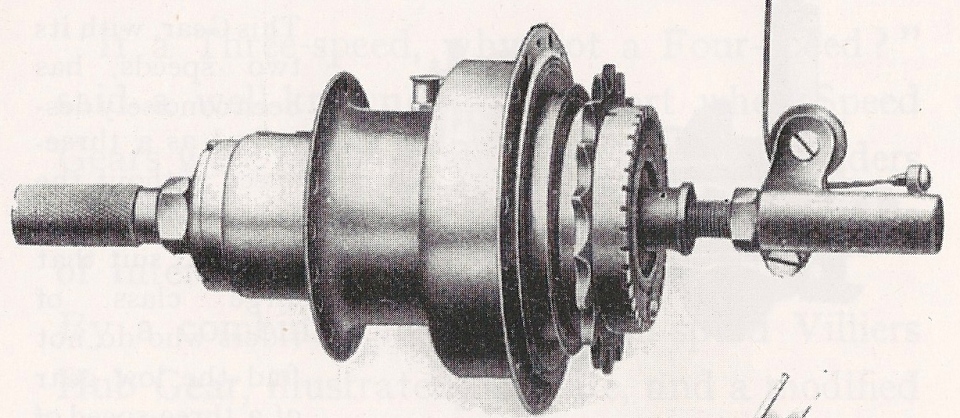

Sunbeam’s own design ‘was introduced to the Cycling World in 1906’ as the catalogue rather grandly puts it, adding that ‘It has given complete satisfaction’. One contemporary authority, FT Bidlake, described it as ‘a beautifully made article – more expensively produced than most Gears’. Yet by 1913 it had disappeared, replaced by a version of the BSA 3 speed, which was in turn a modified form of the Sturmey-Archer X-type.

Mind you, most of the other makes of hub had disappeared by that time too: Sturmey-Archer dominated the market, with BSA (producing a Sturmey-Archer design) their only serious rival, a situation that was confirmed by 1918 after the interruption of the war. Competition may improve the breed, but only temporarily; an untrammeled market will eventually tend towards a monopoly, or domination by a few large players. So was the Newill three-speed simply a victim of market forces? It seems unlikely.

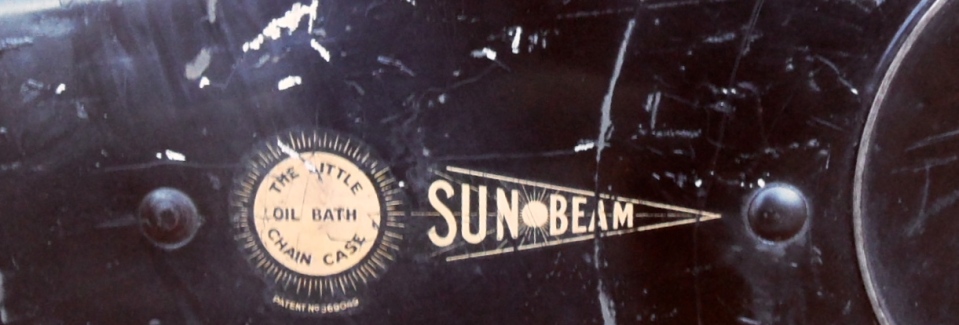

Sunbeams were aimed unequivocally at the high end of the market. They were very costly and took pride in being distinctive: the bicycles bristled with patents, from the design of the brakes (at least two patents) the ‘little oilbath’ gear-case (at least three in addition to Carter’s original patent) the aluminium pedals and the patent anti-theft headlock; in addition, Sunbeams were innovative in using alloy rims (made from Romanium, a patent aluminium compound) and their consistent championing of the bottom-bracket gear. In 1908 they asserted (using a slogan long associated with Rover) that ‘The Sunbeam Bicycle has now for many years set the fashion to the Cycle World’. A firm so dedicated to going its own way would scarcely abandon their patent three-speed gear (which had many novel features, including the eminently sensible one of reverting to direct drive if the wire failed) purely from commercial considerations.

Another possibility is that, for all the praise lavished on it, the Newill hub had some flaw that became evident with use, so that after a few years, it was quietly withdrawn. There are a couple of things that point in that direction, though neither is conclusive. The first is that the original design was altered between 1908 and 09: where the patent shows an axle with three splines engaging in a clutch housing with three slots, the later hub (of which mine is an example) has a four-spline axle and a four-slot clutch housing. The proportions of the clutch housing also look different – the later one seems shorter – and that is reflected in a change in outward appearance: the hub casing in the original has four diameters, starting with the widest at the r.h. or sprocket side and reducing to the next by a sharply defined step; then comes the flange for the spokes, with the third and and fourth diameters projecting beyond the flange on the l.h. side. The later hub actually has five diameters, with a more rounded ‘bottle-shouldered’ step between each; the first three lie between the flanges, while the two smallest project beyond the flange on the l.h. side, but not so far as in the original. This new shape first appears in the 1909 catalogue, although as can be seen by comparing the catalogue picture with the photograph, the depiction is slightly fanciful, more sharp-edged than reality:

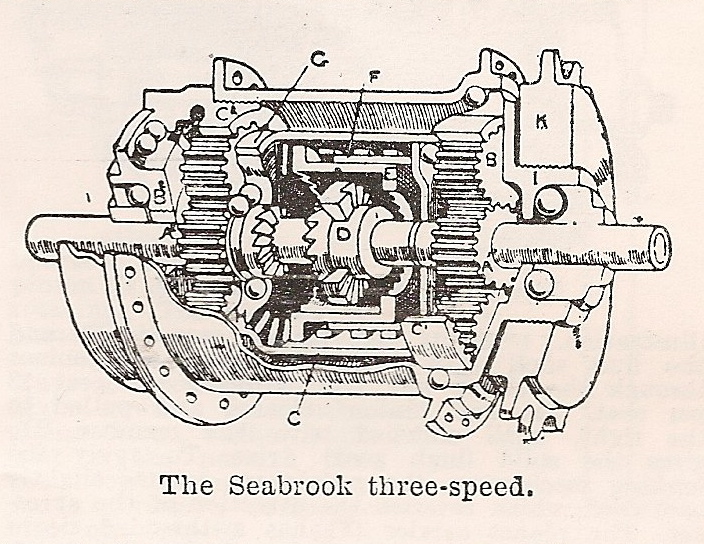

The second suggestion that all might not have been well with the Newill hub is that Sunbeam filed a patent for an entirely new design of hub gear in 1907, in the name of the Villiers Company. Charles Marston and James Morgan are named as applicants, but not William Newill. This patent centres on ‘a simple method of effecting the direct drive in such change speed gears’ and employs a form of clutch different from that used in the Newill design. (It is interesting to note that my own hub has a problem with the direct drive, but on the other hand it is over a hundred years old, has seen some wear and tear and been stripped down and reassembled by an amateur – me.) It is hard to think that Sunbeams would have gone to the trouble of fillng another patent unless they thought it an improvement on the original. However, this hub – which to my eye closely resembles the contemporary Seabrook hub – seems not to have been manufactured.

This perturbation around the year 1908 might explain another oddity related to the Newill hub – In later years, Marston’s seems to have forgotten how long they manufactured it for: Robert Cordon Champ’s article mentioned above was prompted by a note in a Marston’s leaflet of 1933 suggesting that the Sunbeam three-speed hub ‘was not fitted after 1909’. Yet it features in the 1910 catalogue and there are several bicycles in existence, some from as late as 1912, which are fitted with it. But (if we go by the catalogues) it is true to say that the original Newill hub, with the three-spline axle and the sharp-stepped casing, was not fitted after 1909, the year the modified version first appears in the catalogue.

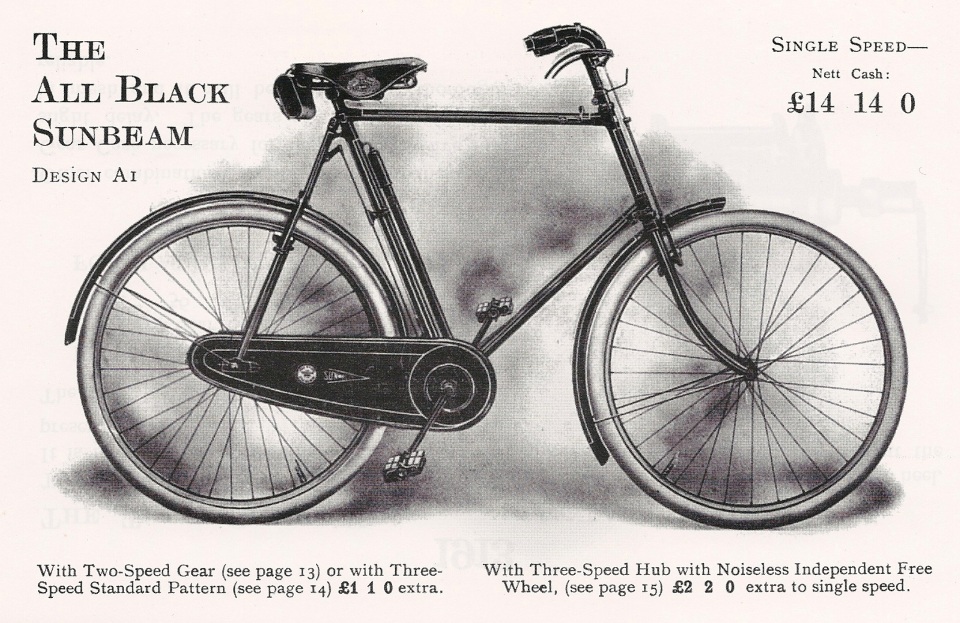

It was in searching for the latest mention of the Newill hub in Sunbeam literature that I came across another possible explanation of why it might have been dropped, one that I find persuasive. The admirable National Cycle Collection website has a fine on-line library which is free to V-CC members. As well as catalogues for 1906-1910, all of which feature the Sunbeam 3-speed, there is a curious booklet entitled ‘The Revolution in Cycle Finish’ which the NCC dates to 1912. This includes not only an illustration of the late-model Newill three-speed but plainly states that it is available as an option on the ‘All-Black Sunbeam’ for which there is an advert at the end of the booklet – so if the NCC’s date is correct, this is clear evidence that Sunbeam’s own hub was still offered as late as 1912. But the manner in which this information is presented is curious, to say the least.

There is nothing new under the sun, as Ecclesiastes remarked, and the idea of dressing up advertising material as ‘independent’ health advice – so common now on the sidebar of social media websites – was around a century ago (and well before that, I am sure). The catchily-titled booklet ‘THE REVOLUTION IN CYCLE FINISH – and how it will aid one to keep well in Winter – BY A HEALTH EXPERT’ (price threepence, supplied with the compliments of the Sunbeam Cycle Depots 157 &158 Sloane St. ) has as its frontispiece a sequence of three pictures. The first shows a nattily-dressed gent in bowler hat, overcoat, trousers, socks and shoes – the absence of cycle-clips is evident – riding (with a somewhat dispirited stoop, it must be said) a bicycle which just happens to be a Sunbeam, alongside the caption ‘How influenza is avoided.’ Below that is the picture of a tram, captioned ‘where influenza is caught’ while the third picture shows railway carriages wreathed in steam with the invitation to ‘see page 9 ’ (where we find a cartoon of a man in a top hat sandwiched between two people on a bus, one of whom is clearly unwell; alongside, we are told that ‘Cold winds and damp assist in the general lowering of health, and renders one susceptible to disease; but it is our modern public Conveyances, our ‘Buses, Tramcars and Trains, which form the breeding-grounds for the spread of Infection.’ [the author has a penchant for capitalising any word he thinks important]

For some eleven pages, the ‘Health Expert’ unfolds an ingenious argument in favour of cycling throughout the year: it makes the most of the weather; it has numerous health benefits, mental as well as physical; it is better for us than motoring; it helps with other hobbies; it is by turns a sport, a means of locomotion, a way of avoiding distasteful idleness and has the virtues of convenience and independence – all of which leads him to the overwhelming question,

‘why in the name of health, pleasure and economy should we not

CYCLE ALL THE YEAR ROUND? ’

To which, it appears, there is but one major obstacle – it is not the man who is unequal to the task, but his machine. In a section entitled ‘THE BUTTERFLY BICYCLE’ our health expert avers that

‘In most cases, I suppose, the answer to my question would be, “That’s all very well. I’m not made of sugar, and I can stand cold and damp weather as well as most people. But what about the Cycle?”

Here, I think, we reach the crux of the whole matter — What about the cycle?

The bicycle, with the old style of finish, is a butterfly machine. In fine weather, if clean and polished, it is a Joy to look at. In wet, it is — not.’

It turns out that our ‘health expert’ has more than one string to his bow – he knows a thing or two about bicycles as well. Even the best of plated work, he tells us, will not stand up to the ravages of the weather, and this is particularly true of the plated rim; but far and away the most vulnerable aspect of the average bicycle is its driving mechanism, with its exposed cog-wheels and naked chain, which one can only hope to preserve by the impractical course of removing it, soaking it lengthily in paraffin then boiling it in tallow at least once a week – a practice helpfully illustrated by a drawing of a disgruntled-looking fellow seated beside a stove on which a pan is belching clouds of noxious-looking smoke.

Must we then forgo as unattainable the numerous benefits of year-round cycling which our health expert has so tantalisingly held out to us? Not a bit of it! For there is one bicycle, it seems, that has none of these defects – with its fully-enclosed oilbath chaincase, black enamel finish instead of plated parts, rustless aluminium rims and pedals, the new All-Black Sunbeam is truly ‘the “never mind the weather” cycle’.

So, after some fifteen pages – rather more than a third of the way into the text – the writer has finally revealed his true colours as a Sunbeam propagandist. If we now turn to the back, we find a fine illustration of the All-Black Golden Sunbeam (but not in fact this one – see footnote)

together with a detailed specification, which includes

‘GEARS – This model is supplied with either single, two-speed, or three speed – whichever may be preferred – ratios as required. For winter riding it is important to have correct ratios. See page 20 of this booklet.’

Page 20 is the start of a section headed ‘THE VARIABLE GEARS’

which opens with this bold assertion:

‘Two gears are needed for all-the-year-round riding – a gear for hard work and a gear for easy work.’

‘Hard work’ the writer explains, is ‘not merely … Hills, but what is far more important, … head Winds, and … heavy, sticky Roads’.

It is noted in passing that the ‘gear for easy work’ (i.e. the higher gear) ‘is useful in dry weather for riding on the level or even uphill ’ [my emphasis] and we are told that ‘between 62 and 66 will be found best for the hard work, and for the higher ratio something between 82 and 88’ [these of course are not ratios at all, but ‘gear inches’ – and it is no surprise to find that the recommended range is precisely that offered by the Sunbeam bottom-bracket two-speed gear]

The chief point of interest comes in the next paragraph:

‘Some riders prefer three gears, but the value of the three-speed is not so great in practice as one would suppose it would be in theory. Thus there is also always the danger of having three gears, two of which are unsuited to winter use. For example, a three-speed rider usually has a middle gear of about 72, and a low gear of 54.’ (these are precisely the gears recommended in earlier Sunbeam catalogues (from 1907 on) ‘as being most likely to suit the average rider’)

The writer continues, ‘Now, neither of these gears is good in a head wind, because the middle gear is rather too high, and the low gear is rather too low.

Those riders who favour the idea of three gears will find that the best combination is to have the middle gear about 65, with a low gear of 48 and a high gear at 86. It is true that the low gear of 48 will only be required on very exceptional occasions, but it is better to have a middle or direct driving gear that is correct, than to sacrifice the efficiency of this gear for the sake of a low ratio, which. though a little higher, is not high enough for continuous riding.’

In other words, for all the use this lower gear is, you might as well make do with just the 65” direct drive and 86” high gear which the Sunbeam bottom-bracket gear supplies – so it is no surprise to have the writer conclude this section much as he began:

‘For myself, however, I prefer two gears to three – the two-speed is so much simpler and freer from complications; and complications undoubtedly do produce more Friction.’

Now, considered in itself, this is an extraordinary thing – here we have a Sunbeam propagandist – albeit one masquerading as some sort of medical man – briefing against one of their own products; indeed, the text above is divided in the booklet by this picture of a dismantled Sunbeam three-speed

the very article whose worth the writer is calling into question.

It is evident that the three-speed has fallen out of favour at Sunbeamland, though the case made against it is more than a little specious and is really a disguised justification of the two-speed bracket gear. What is going on?

The answer can be found, I would suggest, in the next section, which deals not with gears but ‘THE MANAGEMENT OF TYRES’

Still pursuing the theme of year-round riding, it begins with the questionable assertion that

‘Punctures are less frequent on damp roads than on dry ones’ [so how come so many of my wheel-changing memories are associated with downpours?] ‘But if you have tyre troubles the designers of the All-Black Sunbeam have provided for them.’

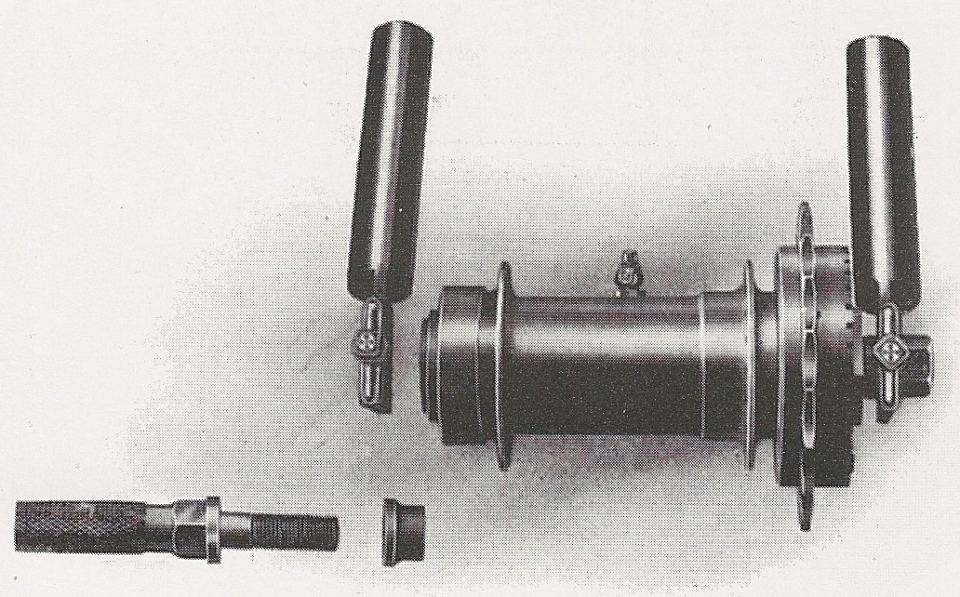

What follows is an exposition of Sharp’s patent dividing axle, which is illustrated, as always in Sunbeam catalogues, with the freewheel fully exposed – in other words, the celebrated ‘Little Oil Bath’ is omitted.

This is slightly odd, since the only real advantage that Archibald Sharp’s ingenious invention offers (and the reason why it was ‘purchased for the exclusive use of Sunbeam riders’) is in conjunction with a fixed gear case – which, as Sunbeam owners know only too well, puts removing the rear wheel on a par with Holy Matrimony: ‘not by any to be enterprised, nor taken in hand, unadvisedly, lightly, or wantonly’.

This is slightly odd, since the only real advantage that Archibald Sharp’s ingenious invention offers (and the reason why it was ‘purchased for the exclusive use of Sunbeam riders’) is in conjunction with a fixed gear case – which, as Sunbeam owners know only too well, puts removing the rear wheel on a par with Holy Matrimony: ‘not by any to be enterprised, nor taken in hand, unadvisedly, lightly, or wantonly’.

But of course, as the writer adds almost gleefully, ‘This invention [Sharp’s axle] cannot be utilised on a three-speed cycle, owing to the intricate internal mechanism of the Hub; this is perhaps another argument in favour of the simpler two-speed.

For there is no doubt that this “divided hub axle,” as it is called, effectually removes the only real objection to the Gear-Case. Formerly, to remove a tyre, a Rider had to open his Gear-Case. Now, the Gear-Case is undisturbed.’

It is curious that Sharp’s axle is presented here as if it were a new solution, whereas it was purchased by Sunbeam in 1905 – the same year that their own three-speed was patented.

But it is the final paragraph of this section that really takes the biscuit, offering the single most bizarre piece of advice I have ever come across in all my reading about bicycles:

‘Riders who will have Three-Speed Sunbeams’ [and note how the insertion of ‘will’ makes that sound an act of headstrong folly] are advised to have Air Tubes shaped like a sausage instead of in one continuous circle. These are not quite as satisfactory as the standard type, but they can be renewed without the assistance of the invention illustrated opposite [i.e. Sharp’s axle] because they are not in a continuous circle.’

(I have to say that on reading this I was immediately reminded of the eccentric savant de Selby from Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman, the only novel in which the romantic lead is played by a bicycle. De Selby, it will be recalled, had a theory that the world was ‘sausage shaped’ . Might that be a clue to the true identity of Sunbeam’s ‘health expert’?)

But seriously – sausage-shaped inner tubes? Who ever heard of such a thing? Was such a thing ever manufactured? Who would even dream of such a thing — ?

Aye, there’s the rub – the only person who could possibly conceive a practical use for a sausage-shaped inner tube is one desperate to find the solution to a very peculiar and specific problem, namely how to overcome the inherent difficulty of fixing a puncture on the rear wheel of a bicycle with a fixed gear-case. The sausage-shaped inner tube – like Sharp’s divided axle – is an invention with a very restricted application; but unlike Sharp’s axle, it is hard to see that it would actually work.

And there, I think, you have the ultimate reason why Sunbeam did not persevere with their own three-speed hub – it exposed the Achilles’ heel of their trade-mark ‘little oil-bath’ gear-case, namely that it makes the common occurrence of fixing a puncture in the back tyre a tedious, protracted and complicated chore. Hence, I would suggest, their initial impulse to consider Newill’s patent as a bottom-bracket gear – with the gears in the front, the problem at the back is solved by Sharp’s axle, which was patented in 1900 and bought by Sunbeam in 1905, the year the Newill patent was registered.

I suspect that by 1912 Sunbeam had had enough of customer complaints that made a weakness of what they advertised as their main strength – in the words of the ‘health expert’ himself, ‘while many cycle-makers have listed a gear-case as an Accessory, one has made it an indispensable part of the machine – I refer to John Marston Limited, the makers of the Sunbeam. They have maintained the necessity of the gear-case since safety cycles first ran’ – and if the ‘little oil-bath’ was an indispensable necessity, then there was not much point in continuing the costly manufacture of a component that only served to expose its one serious weakness – the Newill hub had to go. Henceforward, the ideal Sunbeam would be the All-Black with two-speed bottom bracket gear and Sharp’s dividing axle – a form in which it continued to be offered for the next two decades.

*indeed you do: it was only in reviewing this article once I had published it that I looked closely at the illustration of the All-Black Sunbeam above, which is not from ‘The Revolution in Cycling Finish'(which I could not copy) but from the 1913 catalogue – and if you study the options offered below, you see on the left ‘With Three Speed Standard Pattern (see page 14)’ – a guinea extra – this is the BSA hub, itself a version of the Sturmey-Archer X type; but on the right, ‘With Three Speed Hub with Noiseless Independent Free Wheel (see page 15)’ – two guineas extra. Now, the ‘Noiseless Independent Free Wheel’ is a feature of the Newill hub and there is no doubt that this is simply an alternative description of the very same article – so it was still being advertised and (from the page reference) illustrated as late as the 1913 Sunbeam catalogue, the year in which it was superseded by the ‘Standard Pattern’.

Summer Saddle Mystery

I have acquired a saddle, a bit of summer indulgence. It’s something of a mystery piece.

In general design it much resembles the classic Brooks B90/3, but it is of smaller make all round – the cover is not so large, the springs, though sturdy, not quite so stout and of smaller circumference.

Its proportions are closer to my hybrid B66

Well-made and of uncertain age, it is in sound condition, albeit somewhat crazed on the surface (much like its owner, some might say).

It does, however, have ‘handed’ springs – note how the spirals go in opposite directions, a distinction denied to the two late-model B90/3s in my possession, though I believe they used to have handed springs in the past (certainly, they still list left and right hand springs in their catalogue, though I believe only rh ones are in stock). Note that the rivets are definitely on the rear end of the saddle (unlike the B90/3 where they are more on the top), even though this adds a complication to the design – the cantle plate that they attach to on the inside appears to occlude the saddle-bag eyelets, but in fact it has two bends in it to allow the straps to pass through.

Along with the integral metal-reinforced saddlebag eyelets, a rather more labour-intensive fitting than the separate ones on the late B90/3s, I take that to be an indication that it is fairly old and not cheaply made, but the lack of any branding is curious. The embossed stamp on the flanks conveys little in the way of information:

the surround, where writing might be expected, is a sort of Grecian border, with a bicycle-wheel on each end which makes it look, from a distance, like the earlier versions of the Brooks stamp. The central symbol might be a letter S interwined with a flower,

but there is something in the overall design that looks, to my eye, possibly Indian: could it be from the sub-continent?

Though the integral eyelets and handed springs hint at high-class manufacture, the cut-outs have an oddly amateurish look to them, as if they were done by hand:

All in all, an acquisition I am well-pleased with, though I wish I knew more about it. There is nothing on the saddle clip or elsewhere on the metal frame to give any indication of its origin either. I think I will probably fit it to my 1923 Royal Sunbeam, which came to me with a nice B66 which sadly gave way. Although I like the B90/3, I do think a smaller saddle might look neater.

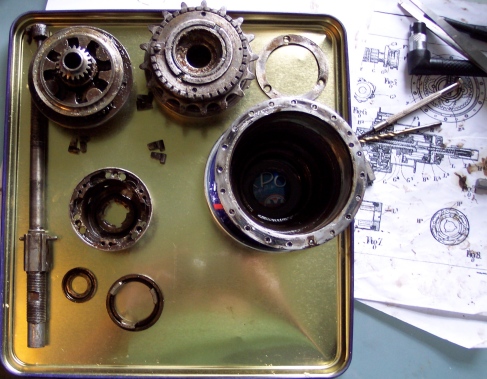

In the belly of the beast

This one is for hard-core hub-gear fans – epicyclists? – only. It shows the dismantling of my hundred-year-old Sunbeam ‘Newill’ hub, which I did a few years ago. At the moment, the sequence is on Flickr as a set, and some of the shots are a bit dark, though if you blow them up, you can see most detail you might want. They are also labelled, so if you mouse over them you can identify the various components. I hope it may be of some technical interest to perhaps as many as three or four other people in the world.

As you will see from the captions, this is something of a mystery story: the gear slips in direct drive, which in theory should be impossible. Looking over it again, I find I had forgotten the extent of the work I had done on it, and the degree to which I had advanced my understanding.

Any of you who have ever done it will know that while dismantling and reassembling an epicyclic hub can afford a great deal of satisfaction (as long as you get it to work) doing it repeatedly eventually becomes tedious (there are no fewer than seven separate sets of ball bearings in the Newill hub, most of them tiny, to say nothing of six pawls and the little hair springs that actuate them) especially when you are trying to run down the cause of a fault that only becomes evident when the hub is in operation under load, on the bicycle – in other words, every time you put the wheel in place (no small task in itself, though a great deal easier on a Pedersen than a Sunbeam) your heart is high with hope – this time it will surely work! This, time, surely, you have eliminated the fault!

But no, you haven’t, and it doesn’t, but in the end you leave it in place and put up with it (it is an intermittent fault, after all, and you can get by on low gear and high for most purposes) because you cannot face yet another taking off and stripping down…

But now that the passage of time has deadened the pain, and in any case the Pedersen is hors de combat, awaiting a new saddle, I find that my curiosity is sufficiently piqued to give it another go – after all, for any mechanical mystery there must be an explanation – mustn’t there?

So I hope to repeat the exercise some time soon and photograph it better – watch this space. I shall certainly make use again of the original patent drawings as a guide, which I downloaded from the excellent European Patent Office website and printed off. You can view the patent document with drawings here : GB190515579A. Though it might seem daunting, I found it a great aid to understanding when actually working with the hub.

In the mean time, may I invite you to join me –

How many gears does a man need?

(for the map of this route, see here)

This question was prompted by my ride to Elcho Castle on the Dream Roadster (I suppose it also has an echo of the Tolstoy short story ‘How much ground does a man need?’ which is well worth looking out, but I can’t find a link at present).

My love of the epicyclic hub had always been tempered by frustration at its fixed range of gears, meaning they could only be raised or lowered as a group. A tall gear for bowling along at speed means sacrificing hill-climbing power and vice versa. I took it as axiomatic that more gears were better till I got my first Sunbeam. This was a 1923 model, fitted with the ‘standard’ Sunbeam hub* giving gears of 56″, 73″ and 96″ – yet I could ride this bicycle up Stephen’s Brae in Inverness, a short but steep incline which had defeated me on other machines. Doubtless the geometry (it’s a 26″ frame) and the clean permanently-lubricated drive-train in its oil-bath helped, as did the fact that simply being on that bike made me feel happy, but it did make me question for the first time whether more gears were necessarily better.

So, bearing that in mind and after my experience on the Elcho Castle run, I resolved next day to make a trip on my other Sunbeam, from 1934, which has a Sturmey Archer K-type 3-speed hub.

But first I had to fix one of those niggling problems that can (when you are in the wrong mood) provide an excuse for not going out on a particular bike. The left-hand brake lever (which in usual Sunbeam practice, but unlike most other British bikes, operates the front brake) was able to slide sideways in its bearings, rendering the brake inoperative. Close inspection showed that there was a little grub screw which was intended to locate the lever in a slot on the underside of the bearing, but it had sheared off, leaving the remnant in the lever. So I detached the lever and drilled it out (having tried to free it by other means, in the hope of preserving the thread in the hole) and solved the problem in brutal but effective fashion by inserting a small screw through the slot and jamming it into the hole in the lever.

I had no definite plan in mind, but I thought I might complete the journey to Almondbank which I had started but abandoned on the Dream Roadster shakedown trip. I duly set out and made a long diagonal across the South Inch, one of two broad expanses of green between which Perth lies,hence the old jest that it is the smallest town in the world because it lies between two inches. On the corner of Tay St. I paused for a picture outside the Fergusson Gallery:

The Fergusson Gallery is a splendid little place, located in the old Perth water works (hence the title above the door – ‘water by fire and water [i.e. steam] I draw’). The upper part of it is said to be the oldest cast-iron building in the world. Despite the name, it is devoted as much to the works of Margaret Morris, John Duncan Fergusson‘s wife , an artist in her own right and a pioneer of modern dance. Well worth a visit.

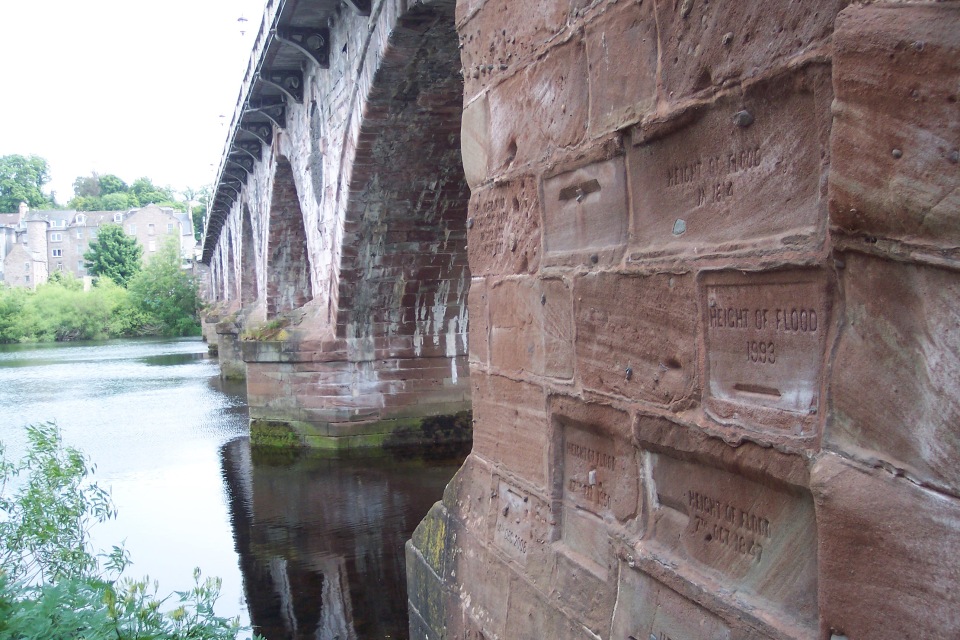

From there, I went along Tay St, which runs by the river as its name suggests – along with much interesting street furniture and some fine sculpture, the most striking things are the heavy gates of the flood defences, set into a sturdy parapet wall which in my youth was just railings that you could get your head stuck in. The need for the flood defences becomes evident if you pause under the arch of the Old Bridge, where various high water marks are carved:

(click to view large and read the inscriptions)

This gives an idea of the normal water level, and allows you to imagine the sheer volume that must have been required to raise it to the flood-levels shown:

Bear in mind that for many of the floods, the bike would have been entirely submerged, and yet the path it is beside is at much the same level as the huge expanse of the North Inch that lies beyond it, though this has now been protected by raising mounds along the edge of the path.

The path runs some distance with river on one side and the green expanse of the Inch on the other, then turns and follows the Almond where it joins the Tay up past Woody Island. Though people call it the River Almond, that is a redundancy – Almond (which is a common river name in Scotland) means river, and is (I believe) cognate with ‘Avon’. This stretch of path is a pleasant one, particularly at this time of year, when everything is so green and lush.

My attention was caught by this tree, which had a wild rose growing up through it, right to the top – sadly, the pictures don’t do it justice: it was beautiful.

There is something very attractive about a narrow path between green banks, especially one that disappears round a bend some way ahead – it leads you on…

(The tag on my handlebars, by the way, is from the auction where I bought the bike, which happened to fall on my birthday. I wasn’t able to go and left an absentee bid. I was delighted to return and find I had won the Sunbeam, along with a little Lady’s Raleigh, part of the same lot. I’ve grown fond of the tag, for no particular reason, and have left it on)

Some way along, you come on this spectacular scene of erosion. The opposite bank is about twenty feet high, and at some recent time a large portion of it has slid into the river, bringing with it a couple of good-sized trees, which you can see in the foreground; the solitary rather bare and dead-looking tree that remains looks none too securely fixed.

If you click on the picture above and maximise it to the full, you will see that the top of the bank at the right hand side is riddled with little burrows, which are the nests of sand-martins.

These were diving and swooping at a great rate and in great numbers over the water, doubtless catching insects (or perhaps spiders – I heard recently (here, in fact, on the marvellous Tweet of the Day) that swifts’ diet is composed very largely of tiny spiders, which they catch in mid air – the spiders seemingly spin out a long thread of silk and the wind catches it and bears them away through the vast spaces of the upper air – which for them must be every bit as heroic as space -travel is for us, with rather fewer resources. Perhaps I should write a book with a spider hero evading ravenous giant swifts…) (though I do love swifts – my favourite bird I think – they give such an impression of the sheer joy of flight)

It’s striking that the tree in the left foreground, which is actually lying horizontal, its crown towards us, (having presumably started life much higher up the slope) is still so abundantly green, while its upright companion at the top looks very forlorn and dead. If you click on the picture below and enlarge it to the full, you will see a sand martin high up in the top right corner (‘the postage -stamp corner’ as footballer commentators of old used to term it, when describing where a shot went into the goal)

It’s moments like this on cycling trips that make you wish you had the skill of Frank Patterson, whose effortless line drawings capture so well the many and varied delights of cycling, especially in country lanes (galleries of his art here and here and here) :

And the Sunbeam does look rather well, does it not, for all its non-regulation red rims and showy cream Schwalbe Delta Cruiser tyres?

I’ll hazard a guess that this sad remnant has something to do with the Perth, Almond Valley and Methven Railway, which received Royal Assent in 1856, was closed to passengers in 1951 and to all trains in 1965, the direful year. Perthshire used to have a network of branchlines that must have been among the prettiest in the country, if you follow their routes on old maps:

Here we are approaching the weir that forms a reservoir to feed the Lade, a stream that was created over eight centuries ago to take water from the Almond through Perth, debouching in the Tay, to provide power for numerous mills, a project that proved eminently successful.

This is the sluice gate that controls the flow into the Lade:

And this is the barrage across the Almond which creates the reservoir to feed the Lade – the river flows through the narrow channel in the right middle ground, while the sluice gate is located below the left bottom corner:

and this is the rather humble beginning of the waterway that in many ways founded the fortune of the town:

If you look at the map of this route (and bring up the profiles by putting ‘elevation’ on ‘large’), you will see that there is a stiff climb out of the glen of the Almond on the North side, which starts a little before mile 7. This was the first real challenge on the run, the first posing of the question ‘how many gears does a man need?’ – and (though it cost me some exertion) the answer in this case was ‘three will suffice’ – I made it all the way up without having to dismount and push. A little after mile 7 there is one of those respites that are so important in cycling – you sweep down a fine short hill into Pitcairngreen, a pretty village that is more English than Scottish in appearance, with its large eponymous green in the centre. I was aware as I descended of a wonderful swathe of colour on my left, where there was a great bank of poppies –

I had already swept past them and reached the junction when its struck me that I was doing them a disservice – they merited a photograph at least, so I turned back and took some:

Which is why my bicycle is across the road, facing back the way I had come:

It was fortunate (though it did not seem so at the time) that I had no cash about my person, because I would undoubtedly have joined the people sitting outside the inn on the corner, enjoying their pints – and who knows how far I would have gone after that? More than likely I would have turned and headed home – after all, I was already further than my only specific notion of a destination, which was Almondbank. But instead I pressed on, satisfying my thirst with just the water I had in my saddlebag. A roadsign at a junction promised me 5½ miles to Bankfoot, which seemed a manageable distance, so I went for that. As you can see from the map, this is an undulating route, relieved by numerous downhill sections, though the general trend is steadily upward – ideal cycling, in other words – periods of sustained effort are rewarded by delightful freewheel stretches where you can catch your breath and admire the scenery. I realised as I went along that I was reversing part of the route I had followed some six years before, on my epic voyage from Inverness to Perth on my 1923 Sunbeam, which I will recount another time – though this picture posted on the Brooks website memorialises what was, literally, one of the high points of the journey.

When I came to Bankfoot – having used all my gears but without once having to push – I was delighted to find a Nisa local store in the Main Street which had a free cash machine – blessings upon them! Here is their Facebook Page. (There’s nothing like getting about under your own steam to make you appreciate local services). I bought an egg mayonnaise roll from them for my lunch. It tasted wonderful. And I felt so virtuous that I resisted the temptation of local hostelries and made do with water.

Unlike Pitcairngreen, Bankfoot is a classic Scottish ‘lang toon’ consisting mainly of houses strung out along a single main street. A little way beyond, I met my Waterloo – a tiny settlement presumably so named in patriotic fervour after 1815. This is on the way out – another case of thinking, as I sped on may way, ‘I really should take a picture of that’:

The profile on the map suggests a very stiff climb shortly after this, between mile 14 and 15, though oddly I have no recollection of it – doubtless I was revitalised by my egg mayonnaise roll and the knowledge that with money in my pocket I could potentially stop for a pint at the next available hostelry. What I do remember vividly was this, some distance further along the Murthly Road, a wonderful free display of beauty on the roadside, eclipsing even the fine poppies of Piutcairngreen, by virtue of their variety of colours:

It has been suggested to me that these might be opium poppies, papaver somniferum.

They are certainly beautiful and their beauty is enhanced by their being on the public roadside. To stop and enjoy things like this is one of the rewards of cycling.

As can be seen from the profiles on the map, this part of the route makes for pleasant easy cycling, being a long descent from mile 15 into the valley of the Tay, which is crossed, together with its tributary the Isla, between miles 21 and 22. Both crossings are by narrow bridges controlled by traffic lights, but there is room enough for a cyclist to stop and take pictures, as I did here on the Isla, looking upstream first:

then down, along its last reach before its confluence with the Tay, just around the bend:

Another Frank Patterson moment:

Beyond the bridge, I resisted the temptation to go left and take in the spectacle of the Meikleour Beech Hedge, a local wonder – it is an impressive sight to see, but not easy to capture well in a photograph. I had been before when I did a variant of this route in reverse on my 1923 Sunbeam a couple of years ago. Doubtless that run will find its way onto this site eventually, but in the meantime you can see it here. Instead I turned right along the A93, which in the other direction will take you to Braemar by the Devil’s Elbow (what’s left of it) and the Cairnwell, the highest main-road pass in Britain. But in the Perthward direction it’s a pleasant undulating cycle, with every climb compensated by a downhill stretch, it seems. For all that, I was glad to see this sign at a bend in the road, and shortly after pulled in to the Strawberry Shop, for a spot of afternoon tea (but without the tea). This is in the heart of Scotland’s finest soft-fruit growing district.

For now, raspberries and ice cream… and some strawberries to take home for later:

The Strawberry Shop itself, with a polytunnel next to it – these have greatly extended the fruit-growing season in these parts.

Finally, on my way home, passing Scone racecourse on the eve of the Summer Solstice, I could not resist a picture of this rather premature advertisement – some sort of record, surely?

The Sunbeam has no mileometer, so the first thing I did on returning home was map my route on http://www.mappedometer.com/ an excellent site of great utility. I was gratified to find it came out at 33.7668 miles – just as well I did not have the means to buy a pint in Pitcairngreen. And how many gears does a man need? On the evidence of this trip at least, three is sufficient.

*The ‘standard’ Sunbeam hub succeeded the ‘stepped’ Newill hub about 1912. Its characteristic feature is that the wire is slack (lever full forward) in low gear, so that you have a better chance of getting home easily should the wire fail. It also has no ‘no-gear’ position (unlike later SA hubs) so there is no risk of a groin-crippling slip when ascending a hill. The hub is in fact identical to the BSA 3-speed, itself a version of the first successful Sturmey Archer hub, designed by William Reilly, and later marketed as the X-type after Frank Bowden and Co had done Reilly an ill turn and swindled him out of his patents, a sorry tale well-documented in Tony Hadland‘s excellent book, The Sturmey Archer Story – now sadly out of print, it seems – I got mine from Old Bike Trader. (but it may still be available through the V-CC)